Introduction

On August 30, 2023, the Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation (“IndyGo”) held a public-information meeting directed to its proposed Blue Line. The Blue Line is intended to replace existing Route 8. As we explain below, however, that meeting provided little reason to believe that the Blue Line will be much of an improvement, at least not enough of one to justify its massive capital expenditure. And the meeting left the nagging impression that the Blue Line will simply repeat some of the problems that have plagued the Red Line.

BRT

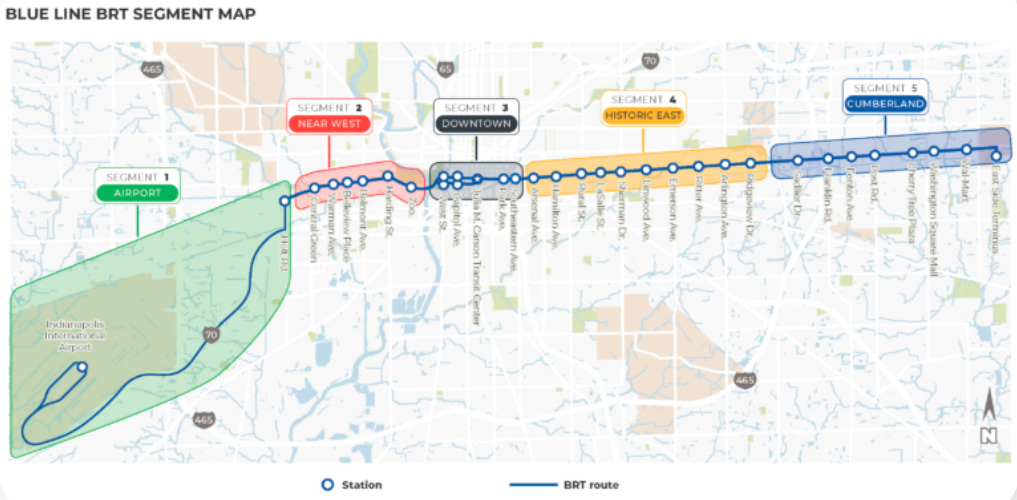

Existing Route 8 runs mainly along Washington Street between the Indianapolis International Airport and the Cumberland Meijer location. The Blue Line will, too, but it will operate as a bus-rapid-transit (“BRT”) route. Among other things, the BRT designation means the Blue Line will implement three time-saving measures that Route 8 doesn’t.

The first such measure is that along much of its route the Blue Line will deprive other traffic of two lanes that motorists currently share with Route 8 buses. Once the Blue Line begins operation, that is, those lanes will largely be dedicated to Blue Line buses, which should thereby be able to avoid any traffic jams the lane loss may cause other vehicles. The second measure is that along its 24.5-mile length the Blue Line will have only thirty-three stops instead of Route 8’s ninety-two. The third is that fare collection will take place off-board, before the bus arrives, so the driver doesn’t have to take time out from driving to collect fares.

Additionally, the Blue Line stops will be more elaborate than Route 8’s. In addition to providing the off-board fare-collection mechanisms they will include bus-floor-level platforms intended to provide easy access for wheelchairs and bicycles.

However, the Blue Line, which is to begin operation in 2027, won’t be the first of IndyGo’s BRT Lines. The Purple Line is slated to begin operation next year, while the Red Line has already been in service for four years. And despite four years of experience IndyGo has yet to demonstrate that it can reliably provide that floor-level access and off-board fare collection.

According to the July 2023 board report IndyGo’s Governance & Audit Report No. 2023-2 observed that the spacing between the platform and the bus is often too great for wheelchair entry. Also, “It was clearly observed that most riders board the bus with no intention of paying at the station.” For example, “During one afternoon of riding the Red Line, it was observed that only two riders validated a pass at the MyKey validator.” Moreover, the Red Line stops’ pass-validating and ticket-vending machines often don’t even work. This calls into question fare-inspector reports’ implications that most riders do pay.

Despite that history the meeting materials described no plans to do much differently on the Blue Line. And IndyGo personnel at the meeting professed not to know what ratio Red Line fare payments bear to the number of riders the Red Line’s automated passenger counters actually record. (One representative said he’d email us that information, but that hasn’t happened so far.) Absent such information, we are perhaps justified in speculating that most of the Red Line’s approximately five-rider-per-bus average occupancy consists of non-paying riders. If the Red Line is still experiencing such problems after four years, why should we not expect the same problem on the Blue Line?

Headways

The BRTs were made possible by a transit tax that residents approved in a 2016 referendum. Voters had been told that BRT buses would come every ten minutes, but the Red Line’s peak frequency actually is only once every fifteen minutes, and IndyGo representatives have now said this would be the Blue Line’s peak frequency, too. This isn’t much of an improvement; Route 8 already provides this frequency on its eastern stretch, although its buses come only half as often on its less-popular western stretch.

Not So Fast

An IndyGo representative said that the Blue Line’s end-to-end travel time will be 55–65 minutes, for a 25–35% reduction from the current Route 8’s. But it seems possible that the Blue Line won’t actually save riders any time at all.

For one thing, IndyGo personnel are just not very reliable. During a similar meeting held on May 6, 2019, for example, IndyGo representatives said that the time required to traverse the Red Line’s entire length would be between 37 and 45 minutes. Although Google Maps says the Red Line may travel the route in about 47 minutes early on a holiday, however, it also says that something like 54 minutes is more typical in the middle of a weekday morning.

Also, even though IndyGo has had four years to iron out start-up problems the Red Line’s dedicated lanes still haven’t provided a speed increase as large as referendum voters had been led to expect. The Red Line route is almost all dedicated lanes between the Broad Ripple Station and the Transit Center, yet late on a Tuesday morning that stretch’s duration is the same as that of a trip to the Transit Center from Broad Ripple & Carrollton Avenues on mixed-traffic Route 18—which has almost twice as many stops and makes a westward side trip to Butler University.

Still, the 55–65-minute prediction is plausible, so we’ll accept it for the sake of discussion. However, IndyGo’s claim that this is a 25–35% reduction would imply that Route 8 currently takes about 85 minutes, whereas the time given by Google Maps for the end-to-end Route 8 trip is often only about 75 minutes and sometimes as little as 72 minutes. Moreover, the Blue Line achieves some of that reduction by lopping off Route 8’s twenty-six-stop Washington Street stretch west of Holt Road, where the Blue Line will take the Interstate instead. If Route 8 were similarly altered so as to make an apples-to-apples comparison it would probably take about 6 minutes less than it does now, making the end-to-end travel time about 69 minutes. Instead of the 20–30 minute savings IndyGo implied, that is, it would be more like 4–14 minutes.

And that’s for a 24.5-mile end-to-end trip, whereas the average IndyGo ride is only 4.4 miles in length. We might therefore estimate that the average rider’s time savings would be only on the order of 0.7 to 2.5 minutes, i.e., 4.4/24.5 times as great as the whole route’s 4–14 minutes. That smaller range’s importance becomes apparent when we remember that having only 29 stops on the 14.1 miles east of Holt Road instead of Route 8’s 64 adds about a quarter mile to the average distance between stops and thereby makes riders walk farther. An additional eighth of a mile of walking could cost the rider around two-and-a-half minutes and thereby make the average Blue Line trip as long or longer than the corresponding Route 8 trip.1

Capital Cost

And the time savings we found before taking the extra walking time into account seems meager when we consider the Blue Line’s huge capital expense in light of its small expected ridership.

Now, IndyGo representatives didn’t give a specific number for the Blue Line’s ridership projection. But one representative seemed to say that according to the FTA’s STOPS package the Blue Line’s ridership would be double Route 8’s. Doubling Route 8’s 2022 ridership gives us 1.6 million rides per year, which at 0.7 to 2.5 minutes’ savings per ride gives us an aggregate annual time savings over all riders of between around 20,000 and 70,000 hours.

This is hardly impressive when we consider that according to IndyGo $185.5 million of the Blue Line’s $370 million capital cost will come directly from local taxes. That’s $185.5 million that residents could instead have put in their retirement accounts. At 5% per annum the resultant opportunity cost would amount to between $136 and $476 per saved riding hour. If we include the capital expenditure’s federal-funds component—which, remember, IndyGo obtains because local residents’ federal taxes help pay for similar transit boondoggles in other cities—the cost is $271 to $947 per riding hour saved. Do taxpayers really want to spend so much to save bus riders a single hour?

And those numbers are based on one IndyGo representative’s prediction that the Blue Line’s ridership would be double Route 8’s. A different representative said instead that the FTA wants a Blue Line ridership projection that equals the average of Route 8’s pre- and post-pandemic numbers. Averaging Route 8’s 2019 and 2022 ridership values yields 1.2 million instead of 1.6 million, which would make the opportunity-cost range $370 to $1296 per riding hour saved.

Again, moreover, it seems at least as likely that riders won’t save any time at all; we came up with those time savings by accepting the IndyGo travel-time estimate and ignoring the increased distance between bus stops.

Empty Lanes

An implication of an August 2020 IndyGo Purple Line presentation was that the Purple Line will cost motorists more time than it saves bus riders. Perhaps because IndyGo eventually came to realize this, the Blue Line meeting provided no similar estimate of how much time its appropriation of Washington Street lanes will cost that street’s motorists. But we do know that lanes currently conducting considerable traffic will become largely empty when the Blue Line begins operation; any given location on a dedicated lane will be vacant for fifteen minutes at a time.

Of course, when buses do come they’ll carry more passengers on average than a car would. But we’d estimate an average occupancy of only about 5.5 passengers per bus. (That results from dividing the product of 1.6 million rides and 4.4 miles per ride by the 1,313,100 vehicle miles we’d expect of the 24.5-mile Blue Line because the 13.1-mile Red Line traveled 702,100 vehicle miles in the twelve months through June 2023.) So the average interval between bus riders traveling in a given direction would be on the order of 2.7 minutes (15 minutes per bus divided by 5.5 passengers per bus). We haven’t consulted the relevant traffic records, but casual observations suggest that this is probably an order of magnitude greater than the current average interval between car passengers.

In other words, transportation capacity that Indianapolis can currently use will largely go to waste once the Blue Line begins operation. This can’t help but reduce Indianapolis mobility.

Expensive Buses

A handout provided at the meeting said that switching from electric buses to hybrids “reduces projected vehicle cost from $128 million to $35 million.” This raises three questions.

First, if IndyGo could save $93 million on the Blue Line by using hybrids instead of electrics—nearly $100 apiece for every man, woman and child in the city—why didn’t it do the same thing on the Red and Purple Lines? Now, part of the reason may be that IndyGo is no longer permitted to buy buses from the Chinese as it did for the Red Line, and other suppliers’ electrics have less range and therefore necessitate higher bus counts. (At a March meeting of the Indianapolis City-County Council’s Municipal Corporations Committee IndyGo’s CEO said the count had reached fifty-three.) But that can’t be the whole story. At the Blue Line meeting an IndyGo representative said the 24.5-mile Blue Line would need only eighteen hybrid buses, whereas even with those Chinese electrics IndyGo (apparently) needed thirty-one buses for the 13.1-mile Red Line.

The fuel savings can’t be the justification for sticking with electrics, because the price difference between hybrids and electrics would probably cancel the fuel savings even if the Blue Line could get by with just as few electrics as hybrids. Specifically, if the above-mentioned prices and quantities are any indication, then electric buses cost about $473K per bus (≈ $128 million ÷ 53 buses – $35 million ÷ 18 buses) more than hybrids but save only about $412K per bus in energy if over a 540,000-mile life those sixty-foot hybrids get 3.5 miles per gallon of $3.50-per-gallon diesel fuel and electrics consume 2.5 kWh per mile of 9.5¢-per-kWh electricity.

Under those assumptions, moreover, the savings in carbon-dioxide emissions at the Biden administration’s $51/t “social cost of carbon” comes to only about $80K if diesel combustion emits 22.45 pounds of carbon dioxide per gallon. Adding that quantity to the energy savings does give electrics a slight edge, but only about $20K per bus, which is down in the noise and far less than enough to justify an electric-bus count greater by even a single bus than the required number of hybrids.

A second question is why IndyGo couldn’t just use conventional forty-foot hybrids instead of those sixty-foot articulated ones. Even if the Blue Line doubles Route 8’s ridership it will carry only about 40% of the 11,000 daily riders IndyGo planned for when it chose sixty-footers for the Red Line. True, IndyGo wants custom buses that have special doors for platform-level boarding. As we observed above, though, four years of experience gives us no reason to expect IndyGo will ever really master that feature.

Moreover, Indianapolis managed for over a century without it, and those custom buses seem unnecessarily expensive. If an IBJ article is any indication, the forty-foot standard diesel buses that Route 8 uses cost on the order of ($7.5 million ÷ 13 ≈) $580 K per bus a couple of years ago, whereas that $35 million for eighteen sixty-foot hybrids translates to $1.9 million per bus: if IndyGo’s numbers can be trusted the Blue Line buses may be more than three times as expensive as conventional ones.

The third question is the following. True, the Blue Line’s bus count will be much lower than the Red Line’s—eighteen hybrids for the Blue Line’s 24.5 miles versus thirty-one Red Line electrics for a mere 13.1 miles. But doesn’t that count still suggest that the articulated buses are hard to keep operational? Let’s take IndyGo’s upper end-to-end travel-time value, 65 minutes, and add a 10-minute break after each trip. That makes a round trip 150 minutes: theoretically, the Blue Line would require only (150 ÷ 15 =) ten buses if they come every 15 minutes. So that means eight spares for ten buses in use—even if the Blue Line’s speed barely exceeds Route 8’s. If it's significantly greater, then there could be one bus in reserve for every bus in operation.

Either way, the large number of spares suggests that IndyGo may expect to have a hard time keeping those articulated buses in operating condition. That problem may be exacerbated by the fact that if the Red Line’s record is any indication those sixty-foot articulated buses will be particularly collision-prone.

It just seems that IndyGo has been saddling itself with more complexity than it’s competent to handle and as a result is subjecting residents to unnecessary expense.

Conclusion

Despite the projected travel-time reduction, nothing the Blue Line meeting presented gave us any reason to expect that the Blue Line will save riders nearly as much time as it will cost motorists. And four years’ experience with the Red Line suggests that the promised wheelchair and bicycle access will be a sometime thing and won’t justify the high cost of custom buses. True, the Blue Line’s more-elaborate bus stops will likely attract some ridership that Route 8 hasn’t. But much of that increase may consist of the type of rider who evades fares and whose presence for all we know will discourage residents who previously rode Route 8.

Perhaps the Blue Line project should be abandoned or at least postponed until such time, if any, as IndyGo finally gets the Red Line sorted out.

Instead of an eighth of a mile in total and therefore two-and-a-half additional minutes the post as originally published mistakenly referred to adding an eighth of a mile to both ends and therefore an additional five minutes. These are just estimates, of course, but we believe that the revised quantities are more likely.

Let's all tell the truth. The reason we have this system is not because it's a good idea, but because this is what IndyGo can get money for from the federal Department of Transportation.

If our goal was to help people with transit needs based on the money we have, we wouldn't be building more fixed-route mass transit. We just don't have the density. Instead, we've be spending more on paratransit, on subsiziding peer-to-peer rideshare programs, on housing vouchers so people can live closer to work and not need transit, and more.

But there isn't the money for that in one place, so we've built and will continue to expand a BRT system that is barely used by anyone.