Sen. Braun, You Need to Read This Book (Part I)

Climate-Science Research Isn't As It's Been Portrayed

A previous Naptown Numbers post described the baselessness of one critic’s attack on Steven E. Koonin’s new book, Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters. Such attacks were no doubt expected; by providing much-needed context in clear and accessible terms, the former Obama Energy Department undersecretary for science showed that actual climate-science research bears little similarity to its popular portrayal.

While one critic has contended the science is settled enough to justify taking action, another said to the contrary that the profound uncertainties themselves justify action. Between this post and one that will soon follow we argue instead that the uncertainties make measures such as a carbon tax likely to do more harm than good. Along the way we reprise our discussion of the book’s background, dispose of a couple of criticisms, and show that the climate establishment’s own reports undermine the notion that a climate catastrophe is likely.

As the previous post explained, Dr. Koonin was shaken in 2014 by what he found when his chairmanship of an American Physical Society (“APS”) committee set him to analyzing just what the scientific basis was for the anti-emissions efforts on which he’d spent a decade. The committee’s task was to reissue an expiring APS climate statement. Issued without a vote of the APS membership, the original statement had characterized as “incontrovertible” the purported evidence that failure to take action would result in significant disruption of the Earth’s physical and ecological systems.

The expiring statement had led to controversy and some resignations, so its reissue needed to be bullet-proofed. But in digging deeply Dr. Koonin found that the scientific basis for the APS statement wasn’t nearly as solid as it had been portrayed. His scientific integrity overcoming his political leanings, he began in 2014 to speak out about what he was finding.

Nor was such scientific integrity otherwise absent, incidentally, on his end of the political spectrum. Nobel laureate Ivar Giaever was an Obama supporter, yet he resigned from the APS because of that climate statement. Physics giant Freeman Dyson was an Obama supporter, too, but he considered it obvious “that the non-climatic effects of carbon dioxide as a sustainer of wildlife and crop plants are enormously beneficial, that the possibly harmful climatic effects of carbon dioxide have been greatly exaggerated, and that the benefits clearly outweigh the possible damage.”[1]

Regardless of their stature, though, such independent thinkers tend to become targets of usually misleading and often ad hominem attacks. (The example reported in the previous piece is illustrative.) And their views tend to be drowned out by the greater publicity accorded voices that warn of a climate emergency.

Perhaps that’s why less notice was taken than might have been when Dr. Koonin joined two other eminent scientists, William Happer and Richard Lindzen, in filing a climate-lawsuit amicus brief. That brief’s first section was a primer setting forth research reported in the US government’s November 2017 Climate Science Special Report, the Fifth Assessment Report (“AR5”) of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (“IPCC”), and refereed primary literature. Contrary to the popular impression, that research actually supports those scientists’ following conclusion:

[T]he historical and geological record suggests recent changes in the climate over the past century are within the bounds of natural variability. Human influences on the climate (largely the accumulation of CO2 from fossil fuel combustion) are a physically small (1%) effect on a complex, chaotic, multicomponent and multiscale system. Unfortunately, the data and our understanding are insufficient to usefully quantify the climate’s response to human influences. However, even as human influences have quadrupled since 1950, severe weather phenomena and sea level rise show no significant trends attributable to them. Projections of future climate and weather events rely on models demonstrably unfit for the purpose. As a result, rising levels of CO2 do not obviously pose an immediate, let alone imminent, threat to the earth’s climate.

Although the primer attracted less press than it should have, it was brought to Indiana Senator Mike Braun’s attention after the senator’s view had been reported as follows: “‘I just know when you put carbon into the air, it creates a greenhouse effect,’ he said in an interview with [Delaware senator Chris] Coons. ‘That's chemistry and physics. And I think if you keep doing it, it's going to get harder to fix than nipping it in the bud.’” The way in which the climate establishment distorts the question seemed to have made Sen. Braun miss the point. In truth, of course, no serious skeptic doubts the greenhouse effect. The issue is what its implications are.

So Dr. Happer met in person with Sen. Braun to explain what the physics really says. The inventor of the sodium-laser guide star, Dr. Happer is an emeritus Princeton physics professor who specialized in optical and radiofrequency spectroscopy of atoms and molecules and radiation propagation in the atmosphere: he knows more about the greenhouse effect than most if not all climate scientists. (Incidentally, this is common; those who call themselves climate scientists are often less knowledgeable about the disciplines on which climate science depends than many who don’t.)

But science is hard, even for scientists, and science papers tend to be nearly impenetrable. So instead of applying actual science, most people who want to consider themselves enlightened do it on the cheap by following “The Science” (as Dr. Koonin refers to the impressions created by exaggerated climate claims). And nothing in Sen. Braun’s actions since his meeting with Dr. Happer suggests that he’s become an exception. That was perhaps predictable; except by counting heads it’s usually hard for a layman to choose among scientists’ opinions.

But now Dr. Koonin has written a book that sets forth in a way unusually accessible to laymen the logic behind his view that the common perception of climate research is a distortion. The reader needn’t take Dr. Koonin’s word for what that research is, because he cites as bases for his conclusions the same research that the government assessment reports do.

In fact, some of the book’s detractors therefore make the misleading argument that the book provides nothing new, that it merely says what’s been in the assessment reports all along. “But,” says Dr. Koonin, “an assessment report is not a research article—in fact, it’s a very different sort of document with a very different purpose. . . . [A]ssessment reports must judge the validity and importance of many diverse research papers, and then synthesize them into a set of high-level statements meant to inform non-experts.” His book explains why that’s a problem:

The processes for drafting and reviewing the climate science assessment reports do not promote objectivity. Government officials from scientific and environmental agencies (who might themselves have a point of view) nominate or choose the authors, who are not subject to conflict of interest constraints.

A large group of volunteer expert reviewers . . . review the draft. But . . . the lead author can choose to reject a criticism by simply saying “We disagree.” The final versions of assessments are then subject to government approval. . . . And—a very key point—the IPCC’s “Summaries for Policymakers” are heavily influenced, if not written, by governments that have interests in promoting particular policies.

What Dr. Koonin has done is show that the cited research does not support the false impressions that the assessment reports have often used it to create. His book’s theme can perhaps be seen in the passage he quoted from the great Twentieth-Century physicist Richard Feynman’s famous “Cargo Cult” speech:

In summary, the idea is to try to give all of the information to help others to judge the value of your contribution; not just the information that leads to judgment in one particular direction or another.

The easiest way to explain this idea is to contrast it, for example, with advertising. Last night I heard that Wesson Oil doesn’t soak through food. Well, that’s true. It’s not dishonest; but the thing I’m talking about is not just a matter of not being dishonest, it’s a matter of scientific integrity, which is another level. The fact that should be added to that advertising statement is that no oils soak through food, if operated at a certain temperature. If operated at another temperature, they all will—including Wesson Oil. So it’s the implication which has been conveyed, not the fact, which is true, and the difference is what we have to deal with.

Dr. Koonin’s detractors have been creating the impression that Wesson Oil is the only oil that doesn’t soak through, and in a manner accessible to laymen his book explains why this impression is false.

He has written short responses to some of the more-prominent attacks. But it really takes the whole book to provide proper context to the facts (and misrepresentations) that politicians, the press, and celebrity scientists bombard us with. So Sen. Braun would be well advised to read Dr. Koonin’s entire book—and re-read it—if he wants to base his view on more than just The Science.

The senator’s staff may rely on Dr. Koonin’s many detractors for the proposition that the book has been debunked. If so, the senator should critically analyze those detractors’ arguments and ask himself why they would resort to the tactics exemplified below if their case were good.

Many attacks, for example, will be like a Union of Concerned Scientists piece by a Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (“LLNL”) scientist named Benjamin Santer. Protesting an LLNL seminar based on Dr. Koonin’s book, Dr. Santer argued, “Professor Koonin is not a climate scientist. I am.” Unfortunately, much of the public finds that type of argument compelling.

It really shouldn’t. Suppose you’re a Fields Medalist whose concrete contractor has said a six-inch thick pavement for your twelve-yard-by-four-yard driveway will require twenty cubic yards of concrete. Now, you may know nothing about concrete, but you do know that six inches is one-sixth of a yard. So the mere fact that the contractor pours concrete for a living and you don’t is unlikely to make you abandon your view that the job shouldn’t take a whole lot more than (1/6 × 12 × 4 =) eight cubic yards.

And you shouldn’t abandon it; there’s no reason to believe the contractor is any better at the math he uses than you are. Similarly, the mere fact that Dr. Santer spends his days purporting to find a “human signature” in the climate is no reason for believing he’s any better at the underlying math and physics than someone who wrote Computational Physics, taught physics at Caltech for thirty years, and spent a decade advancing carbon-dioxide-reduction efforts (before he dug more deeply into just how weak the case for a climate crisis actually is). The “I’m a climate scientist” argument is particularly suspect when the disputant uses it to prevent the public from hearing the other side.

The book itself describes another type of attack. After the above-mentioned APS committee work, Dr. Koonin undertook further study that led him to write a 2014 Wall Street Journal piece in which he described how shaky climate science is. In the course of explaining how poorly its computer models perform he said, “Even though the human influence on climate was much smaller in the past, the models do not account for the fact that the rate of global sea-level rise 70 years ago was as large as what we observe today—about one foot per century.”

Typical of the type of deceptive article that can always be found to “debunk” those who would interject some nuance into the discussion, a piece by a University of Chicago professor named Raymond Pierrehumbert included the following:

He claims that the rate of sea level rise now is no greater than it was early in the 20th century, but this is a conclusion one could draw only through the most shameless cherry-picking. In reality, according to the data, the sea level trend was .8 millimeters of rise per year from 1870 to 1924, 1.9 millimeters per year from 1925 to 1992, and 3.2 millimeters per year from 1993 to 2014—i.e., the rate has actually quadrupled since preindustrial times.

That statement initially sounds persuasive and comes from someone who wrote a climate book. So we will consider it at some length to demonstrate how those at the center of the climate scare use deceptive tactics to create fear. And by observing the lack of context that characterizes so much of what we hear from that quarter we will see how important the context is that Dr. Koonin’s book provides.

Surveying the magnitude of human climate influences, the nature of our emissions, and the limitations of climate models, Unsettled describes what the actual data say about temperature, weather extremes, and precipitation. More to the point here, it dedicates twenty pages to sea level alone, laying out what we know and what its implications are.

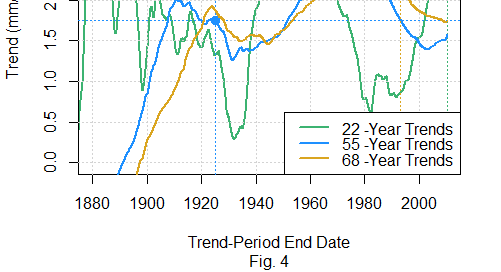

For example, the book says that sea level has been rising, as Fig. 1 illustrates, in fits and starts for nearly twenty thousand years, i.e., since long before significant fossil-fuel use.

It also points out that superimposed on those average values are local differences: “Eugene Island on the Gulf Coast is experiencing a rise of 9.65 mm (0.38 inches) per year, while in Skagway, Alaska, the sea is retreating at a rate of 17.91 mm (0.71 inches) per year.” Continued isostatic rebound, erosion, and subsidence due to, e.g., groundwater removal all contribute to local differences. Add in wave and tide complications and you can see why attempting to assign a value to the rise in global mean sea level (“GMSL”) by backing such factors out involves a measure of judgment and just plain guesswork.

Fig. 2 shows the results of three attempts:

The longest of Fig. 2’s curves shows that sea-level rise resumed in the Nineteenth Century, when the earth began its recovery from the Little Ice Age. Well before carbon-dioxide emissions became significant in the Twentieth Century’s second half, that is, sea level was already rising.

With this as background Dr. Koonin took the plot above from AR5 to show what Dr. Pierrehumbert failed to mention: that acceleration similar to today’s had occurred well before emissions were significant. As yours truly has explained elsewhere, moreover, any recent acceleration will be followed by deceleration if past is prologue.

Yes, such facts had been known before Dr. Koonin’s book, and AR5 had included them. But far fewer of Dr. Pierrehumbert’s readers would likely have looked them up than would have been duped by his omission into thinking that recent short-term accelerations portend a human-caused climate catastrophe.

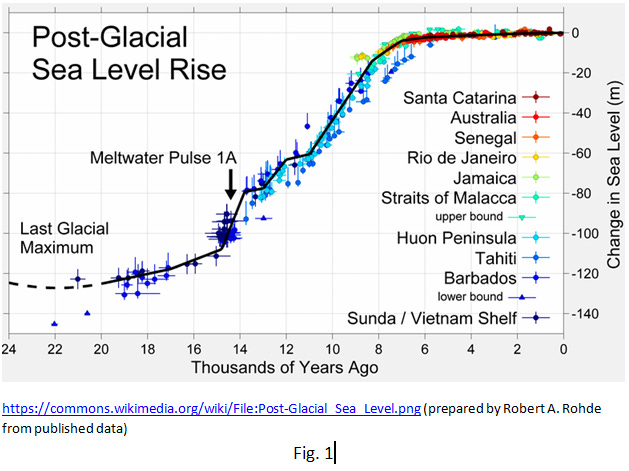

Furthermore, Dr. Pierrehumbert compounded the deception by violating a cardinal rule of time-series analysis: he mixed period lengths when he compared trends. Specifically, he compared the trend of a recent 22-year period with those of earlier 55- and 68-year periods. Anyone who has worked much with time series knows that comparing shorter- with longer-term trends is almost always misleading, because the former tend to vary more rapidly than the latter.

Fig. 4 illustrates this effect by reference to Fig. 2’s longest sequence (which it simplifies by omitting its uncertainty ranges). The y value of each point on Fig. 4’s three curves represents the trend exhibited by the subject sequence’s 22-, 55-, or 68-year period that ends on the date represented by that point’s x value.

Specifically, the leftmost and middle cross-haired dots represent the trends for the first two periods Dr. Pierrehumbert chose: 1870 through 1924 and 1925 through 1992. The rightmost dot represents the trend for 1989 through 2010, which has the same length as Dr. Pierrehumbert’s third, 1993-through-2014 period does but starts four years earlier because Fig. 2’s longest sequence ends in 2010 instead of 2014.

Although Fig. 4 is based on Fig. 2’s longest sequence rather than whatever estimates Dr. Pierrehambert used, the comparison its cross-haired dots represent is like Dr. Pierrehumbert’s in that the first chosen trend is less than the second, which is less than the third: it seems to imply rapid acceleration. Also like Dr. Pierrehumbert’s, though, it’s an apples-to-oranges comparison: it compares the chosen 55-year trend, for example, with the most-recent 22-year trend instead of the most-recent 55-year trend.

If we instead perform an apples-to-apples comparison by following Fig. 4’s 55-year-trend curve to its right-hand end, we see in this case that instead of four times as high as the chosen early value the most-recent trend is actually lower. Similarly, the most-recent 68-year trend is lower than the chosen earlier one.

Of course, we can reverse the comparison by choosing other dates. But Dr. Koonin’s point remains: sea level exhibits variations that the models don’t explain. And it says something about the strength of Dr. Pierrehumbert’s case that to contend otherwise he resorted to such a deceptive tactic.

Nor was Dr. Pierrhumbert alone. Although AR5 did display Fig. 3’s sea-level trends, Dr. Koonin has pointed out that more-recent reports instead tend to employ Dr. Pierrehumbert’s tactic. For example, the U.S. Climate Science Special Report’s executive summary says, “Global mean sea level (GMSL) has risen by about 7–8 inches (about 16–21 cm) since 1900, with about 3 of those inches (about 7 cm) occurring since 1993 (very high confidence).”

Now, perhaps we should avoid attributing to malice what stupidity can adequately explain. But the math required to understand Dr. Pierrehumbert’s subterfuge was well within the ken of any reasonably intelligent layman. And, whether through malice or stupidity, a top climate scientist with stellar credentials seemingly saw no career risk in perpetrating such a readily detected deception. We should bear this in mind when we see projections made by vastly more-complicated trains of statistical inference and manipulation.

Sea-level data aren’t all that’s been misrepresented. Contrary the popular impression, for example, it turns out that heat waves are no more common now than they were in 1900 and that in the U.S. the warmest temperatures haven’t risen in the past fifty years. And the more we investigate claims by Dr. Koonin’s detractors that they’ve debunked such conclusions, the more rickety the climate-science edifice is revealed to be.

Having seen how scientists whose jobs depend on the climate scare can misrepresent the past, we turn in our next post to their speculations about the future.

[1] See his preface to Indur Goklany’s Carbon Dioxide: the Good News