The Indianapolis Star announced yesterday that Purdue University had suspended its Back a Boiler program. That program was set up by a private nonprofit entity called the Purdue Research Foundation, which was established in 1930 to advance Purdue University’s mission in various ways. In the Back a Boiler program the foundation obtained money from Purdue and various investors and used it to finance students’ college expenses through income-share agreements (“ISAs”).

Although the Star didn’t give the reason for the program’s suspension, yesterday’s post was preceded about three weeks ago by a piece bearing the headline “Students feel duped by Purdue's Back a Boiler loan program. Could it be illegal?” That piece exemplified the press practice of withholding information to create false impressions.

To be fair, the Star did accurately describe the basic ISA concept, stating that “a student gets a portion of their tuition paid in exchange for agreeing to pay back a percentage of their future income for a set length of time – usually around 10 years.” It also observed that, “as opposed to private loans that students can pay for decades,” ISAs’ payments end on a date certain. And it said that students whose careers get off to a slow start or who otherwise aren’t earning much can end up paying less than they received in funding. (High earners, who can end up paying as much as 250% of the amount they received, make up the shortfall.)

Moreover, the article related the experience of a grade-school teacher named Savannah Williams, whom it described as “one of a handful of students featured in Purdue's early marketing of the program”:

Williams said she didn't expect to come out of a school with a high-paying job so having payments tied to her income has been a relief. She also has private student loans that she says will take longer than 10 years to pay off.

But the article otherwise emphasized disgruntled graduates whose careers started off with a bang and are therefore paying much more than they had received. And it prominently featured the views of a special-interest group that bills itself as the Student Borrower Protection Center (the “SBPC”).

THIS IS NOT A LOAN

But what the article led off with was an ISA agreement’s all-caps “THIS IS NOT A LOAN” notice. After then outlining the ISA concept, the Star remarked, “The only problem? Income share agreements are private student loans, at least in the eyes of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.”

Schizophrenically, the article also admitted that ISAs can afford advantages over private student loans. But, it said:

[T]he private student loan industry is also highly regulated and has protections for borrowers that ISAs like Back a Boiler don’t have, which watchdogs say is one of the ways the program is breaking the law. For example, traditional student loans aren’t allowed to penalize borrowers for paying off their loans ahead of schedule.

Back a Boiler has no such protection in place. If that student that borrowed $10,000 wants to pay it back immediately upon graduation, they must pay back the “max cap” amount on the contract – typically $25,000 on a $10,000 agreement.

The article went on to say that the CFPB “recently cracked down on another ISA provider for falsely representing that its ISAs are not loans and do not create debt.”

“The ISA industry has tried to evade oversight by claiming that its products are not loans,” said CFPB Acting Director Dave Uejio in a news release. “But regardless of the name on the label, these products are credit and have to comply with federal consumer protections. The ISA industry cannot pretend that core consumer protection laws do not apply to their products.”

It thereby gave the impression that a lot of participants are being duped and that Purdue’s notice is just an attempt to avoid regulatory oversight.

Now, the article did say that Purdue sees things differently:

“Back a Boiler is not a preferred lender arrangement under the Department’s preferred lender rules,” said Tim Doty, director of media and public relations, in the email to IndyStar. “Purdue is proud to offer income share agreements as an income-dependent alternative to private and Parent PLUS loans and thereby assume some of the financial risk our students face in uncertain futures.”

But by providing only generalities like that and omitting important context the Star put its thumb on the scales.

For example, although the Star created the impression that Purdue’s notice makes students more likely to misunderstand their obligations, readers might have formed a different impression if the article had placed that notice’s assertion in its actual ISA context:

This ISA is not a loan or other debt or credit instrument. It represents your obligation to pay a specific percentage of your future earned income. . . .

Just which part of “a specific percentage of your future earned income” is Purdue’s assertion supposed to make students misunderstand? Anyway, it was important for Purdue to give that notice in order to help students grasp the nature of their agreements.

Debt vs. Equity

To appreciate this fact it helps to review how debt differs from equity. Financing terms can be complex, but for present purposes we’ll describe an enterprise’s financing simplistically as provided only by bondholders, who hold debt, and shareholders, who hold equity.

Bondholders have lent the enterprise money and are thereby entitled to payment of (1) the entire principal they’ve lent and (2) the interest that accrues on that principal until it gets paid back. Unless the enterprise goes bankrupt, both amounts are independent of how profitable the enterprise is. (Again, this is simplistic in view of the wide range of financing arrangements, but it’s adequate for present purposes.)

Shareholders, on the other hand, haven’t made the enterprise a loan, so they’re entitled to no principal and no interest. They’ve instead bought a share of future profits. Shareholders therefore risk losing their entire investments. But in return for that downside risk they get rich if the enterprise proves wildly successful, whereas bondholders don’t.

This is why a founder who is pretty sure his enterprise will succeed may choose to be highly leveraged, i.e., why he may want a high ratio of debt to equity: he thereby keeps most of the upside to himself.

But high leverage is risky. Too much debt can drive a start-up into bankruptcy if it’s slow in turning a profit. A founder who wants to shift risk to the financier may therefore grant equity instead—even though doing so may end up requiring the enterprise to pay shareholders many times their original investments.

From the founder’s point of view, choosing equity over debt can accordingly be thought of as making a bet against the enterprise; if the enterprise does poorly it will have received more from shareholders than it ever pays them. Of course, the founder wants to lose that bet even though the loss will make picking equity over debt appear in retrospect to have been a bad choice.

An ISA is like equity in that the investor gets only a share of the “profits,” i.e., of the erstwhile student’s income. And, like the founder of an enterprise that gets funding, the student gives up some upside return in return for protection from downside risk.

The ISA differs from simple equity only in that it’s more favorable to the student and less favorable to the investor. Unlike simple equity an ISA is limited in duration. In the Back a Boiler plan, moreover, the investor’s return is capped at 250% of the investment, whereas common stock ordinarily has no upside limit. But an ISA is otherwise like equity and not at all like debt: there’s no principal to be paid back and therefore no interest that accrues until it has.

So it’s important for the ISA participant to recognize that he’s not issuing debt. If he were he would benefit from inflation: although he would have to return the principal he’d do so with inflated dollars. But the payments he has to make as an ISA investee increase with inflation if his income does. Also, a debtor could benefit from paying the loan off early, because doing so would reduce the time over which interest accrues. But there’s no point in paying a share of future income before it’s earned—even if the participant knew what the income would be—because in an ISA there’s no principal and therefore no interest accrual to be avoided.

If some ISA participants really did mistakenly believe that prepayment would save them money, the cause of their mistake was therefore not the program’s notice that an ISA isn’t a loan. If anything, the cause was instead those participants’ failure to take that notice adequately into account. So by objecting to such notices the CFPB isn’t protecting students; it’s misleading them about what their ISA obligations are. But bureaucrats have more power if they deem ISAs to be loans.

None of that context made its way into the Star’s article. Now, maybe we shouldn’t attribute to malice what ignorance can plausibly explain. It’s entirely conceivable that the twenty-somethings who seem to decide what facts we’re allowed to read in the newspaper are totally oblivious to rudimentary financing concepts. But some of the Star’s other omissions are harder to overlook.

“Marketing Pitch”

For example, where are the specifics of the “marketing pitch” that some families complained of? Here’s what the article said in one case:

Like other families, they say they feel duped by the marketing pitch. They made spreadsheets and did the math on the program and thought it was a good deal. Now, though, the family is looking at paying back the full 250% max cap because their child got a good-paying engineering job right out of school.

Remember, the basic deal is simple: the “child” pays the Back a Boiler program a set percentage of a prescribed number of months’ income so long as the payment total doesn’t exceed 250% of the funding amount. What was it in the “marketing pitch” that suggested the cap wouldn’t really be 250%? The Star didn’t say. Yet we’re expected to believe that the program’s “marketing pitch” prevented students’ families from understanding what is meant by a set percentage of a specified number of months’ income.

Consider in this connection Kaylee Buhr, whom the Star describes as saying “she’d happily pay off something more than the $15,000 she borrowed if she could pay it off today, but thinks the 250% is outrageous.” (Note the category error: Ms. Buhr didn’t “borrow” anything; she sold a share of her future income.) If she thought 250% was outrageous, why did she agree to it?

Her explanation was pretty lame:

“When you’re in college, you’re an adult but when it comes to loans…. You just sign up for this,” said Kaylee Buhr, a 2016 Purdue graduate. “You don’t really know what you’re getting yourself into.”

She said she and her parents, who encouraged her to sign up, feel duped by the marketing. Had they understood this is the position she’d been [sic] in a few years out of school, they’d never have agreed.

Again, where does the marketing say that the cap would be less than 250%? Where does it say that an ISA involves principal upon which interest can be avoided by making payments early?

What Else Did the Star Fail to Mention?

Now, let’s be clear. It’s an unfortunate fact of human nature that not everyone reads contracts thoroughly. So it’s inevitable that certain participants will allow some provisions to escape their notice. But the question is how prevalent such misunderstandings are in the Back a Boiler program’s specific case. And it turns out that the Star omitted information that would have suggested they’re less prevalent than the article made them seem.

This isn’t to say that the Star never mentioned Purdue’s side of the story. But coverage of Purdue’s side was limited to generalities such as the following:

In its response to IndyStar, Purdue said "transparency and ISA literacy are the hallmarks of Purdue’s Back a Boiler program" and the process is designed to ensure students make an informed decision. Participants must also successfully complete a quiz prior to entering into an ISA contract to check understanding.

That sounds much like those bland stands-by-its-reporting responses the press makes when it has clearly misreported things. So the Star leaves the impression that the Purdue Research Foundation had been caught in a misrepresentation.

Had the Star provided more specifics, a rather different impression might have been conveyed. Consider the information that the program’s Application and Solicitation Disclosure gives students before they apply. “Based on your degree level, year in school, and your major,” the disclosure document says, “your income share rate for every $1,000 of funding will be between: 0.173% and 0.497% of your total earned income over a payment term of: 80 to 116 months.”

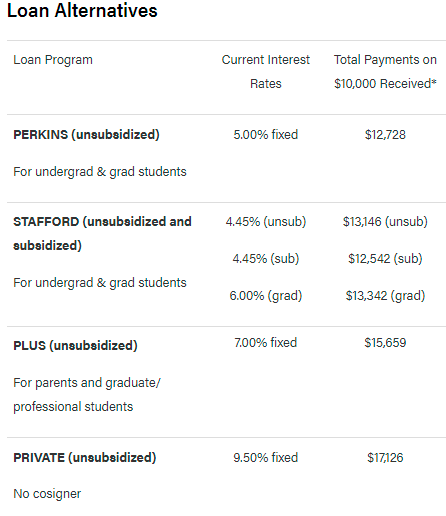

Beyond that the disclosure shows the student what payment totals would result from example ISA terms and rates:

Furthermore, it compares those totals with the totals for sample ten-year-term loan rates:

(The loan totals take into account origination fees and the interest that accrues before payments start.) The disclosure clearly tells the student that the payment totals resulting from, for example, an average of $60,000 in annual income under the mid-range listed ISA terms (3.38% of 100 months’ income) would exceed the funding amount by 69% and fall between the totals for a 7.0% Parent PLUS loan and a 9.5% private loan.

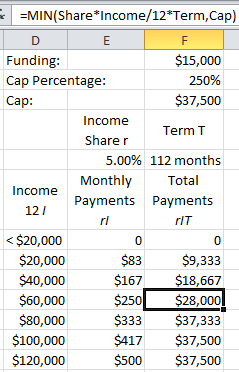

And if Ms. Buhr had “made the spreadsheets and done the math” she would have seen the following numbers for her specific terms:

She would have seen, for example, that her payments would total $28,000, or 87% more than she was funded, if her annual income ended up averaging $60,000 over those 112 months.

But she didn’t have to do the math. Here’s something else the Star neglected to mention: the final disclosure that students get when they execute their agreements would have done the math for her: it would have shown her those very numbers. So she couldn’t have been ignorant of the agreement’s implications unless she’d studiously ignored all the information that the Back a Boiler program tried to convey.

What’s much more likely is that she and her parents actually knew exactly what 5% of 112 months’ salary means and that they considered those terms favorable at the time. The Back a Boiler program is intended for students who might otherwise resort to private loans because they have exhausted grants, scholarships, and federal loans. As the program FAQs state, “The program does not replace government-subsidized student loans, but does offer students another option to pay for their education should they need additional resources or favor a more income-flexible funding alternative. An ISA could be a good alternative to private student loans and Parent PLUS Loans.”

Doing the Math

So let’s consider what Ms. Buhr faced if a 9.5% private loan was her alternative. The monthly payment p for a fixed-payment loan is the ratio A/U that the loan amount A bears to a unit-present-value quantity U given by the following formula:

where r is the annual interest rate, N is the number of payments, and k is the number of months before payments start.

Suppose that instead of selling an income share at the beginning of her sophomore year Ms. Buhr had taken out a loan whose payments didn’t begin until six months after graduation. Then the delay k would have been 39 months, and the payments on a 112-payment 9.5% loan of $15,000 would according to the formula above have been about $275 per month. Instead of the 5% share she pays under the ISA, she’d have been paying 6.6% of her salary if her annual income had ended up averaging the $50,359 that college graduates’ starting salaries averaged in 2016.

True, the ISA would prove more expensive than the loan if her average income ended up exceeding that starting-salary average by more than (6.6% ÷ 5.0% × 100% – 100% ≈) 31%. But Ms. Buhr probably felt at the time that this is the kind of problem she’d like to have; she’d have a good income and would still be paying only 5% of her first 112 months’ salary. That would be much better than paying, say, the 9.5% of her salary the loan would cost if her income ended up being 31% less than the average starting salary. So it ill becomes her now to complain about making payments at the levels she agreed she would if she found herself in such happy circumstances.

We hasten to add that the foregoing comparison was based on average starting salary, and ISA payments differ from a typical loan’s in that they increase as the graduate’s salary does. But a major reason for choosing ISAs is to protect against an excessive payment burden during a rocky career start. A loan could be particularly burdensome to, say, a film-school graduate who has to wait tables for years before he even gets a SAG card. So choosing an ISA over a loan could have been an entirely rational choice for Ms. Buhr even if she thought the ISA’s payments would probably end up totaling more than a loan’s.

That probably was also what Purdue graduate Henry Feldman was thinking when he agreed to pay 10% of 100 months’ income in return for $29,491 in funding at the start of his senior year. The payments on a 9.5% loan for that amount based on a 15-month delay k would be $482.1 True, that would be less than the $662 his ISA payments would average over those 100 months if his annual income averaged the $79,405 median earnings of people between 25 and 34 years old who hold bachelor’s degrees in engineering. But 10% of such engineering graduates average less than $49,799, for which his ISA payments would have been only $398.

Moreover, the starting salaries quoted above are for students who actually graduate, as not all college students end up doing. According to Private Student Loans Guru publisher Mark Kantrowitz less than half of college students graduate on time. Even after six years, he says, less than 60% of students at four-year colleges have earned bachelor’s degrees. Obviously, many never graduate at all.

And failure to obtain a degree is significant. Even when all graduates who hold advanced degrees are excluded, the Bureau of Labor Statistics says that bachelor’s-degree holders average nearly half again the earnings of those who attended college but didn’t graduate. Had the Star included such context, more readers might have concluded that the ISA deals made by people like Ms. Buhr and Mr. Feldman were entirely reasonable under the circumstances.

They might also have taken with a grain of salt the story of a recent graduate who “said he didn’t fully understand what he was agreeing to when he signed a Back a Boiler contract for $10,000 but quickly realized he’d made a mistake.” Again, the final-disclosure documents that students get when they sign their ISAs tell them what the payment totals under their particular terms will be for various average-income levels. More to the point here, the disclosure document begins with an all-caps “RIGHT TO CANCEL” notice and a section that gives the student a cooling-off period during which he can cancel the contract without penalty after seeing those totals.

Providing such context shows that the real story is less the program’s shortcomings than certain participants’ character deficiencies. By choosing ISAs over private student loans those participants were making a bet against themselves. It was a bet that they hoped to “lose,” because “winning” would have meant their incomes would prove lower than they hoped. Yet they’re trying to renege now that they’ve found themselves fortunate enough to lose that freely made bet.

“Wall Street’s Pockets”

Instead of such context the Star prominently featured the views of the SBPC, which has lobbied the Department of Education to shut down the Back a Boiler program. With a heavily left-wing advisory board, the SBPC apparently isn’t a fan of Purdue’s outgoing president Mitch Daniels, who had been a Republican governor. “Purdue students have long been guinea pigs in an experiment that has lined Wall Street’s pockets and stoked Mitch Daniels’ ego while burying borrowers in unaffordable debt,” the SBPC has said.

The SBPC seems to find it offensive that some of the program’s funding sources might have a profit motive. Some of the complaining participants have now embraced the SBPC view in contending that they were misled. For example, the Star said of one parent:

The understanding, they said, was that Purdue alumni fronted the money for the program as a form of altruism, helping out the next generation of students. Those who made good money right out of school would pay back a little more than they borrowed, making up for those who made less and the proceeds would go back into the fund for the next round of students who needed a leg up affording a Purdue education. . . .

This twists the facts. It’s true that Back a Boiler’s goal was to be self-funding. According to one report,

Purdue provided the initial funding along with two nonprofit investors who wanted to encourage new university funding models. The second round, over $10 million from late 2018, included 11 investors and will help the program become self-funding. [The program’s manager] says a third round may be coming.

But the parent who allegedly thought the program was supposed to be “a form of altruism” is also the one the Star said “made spreadsheets and did the math on the program and thought it was a good deal.” How could the mix of funding sources have affected what that parent’s spreadsheets showed?

If the ISA market ever becomes large, moreover, many providers would compete on the basis of the terms they offer, and a profit motive could strengthen the incentive for providers to be as accurate as possible in estimating applicants’ income potentials and thereby the basis on which respective applicants’ terms are determined. That could drive down the variance in payment-to-funding ratios—and thus the frequency of high ratios like Mr. Feldman’s.

Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Of course, the market isn’t large. By using tax money to make rates artificially low, federal loans have left little room for market-priced financing. This has been particularly hard on ISAs. “For this to become a viable additional option . . . we need scale,” said Mr. Daniels. “And we need other schools and many more students participating so that the marketplace of potential investors sees repayment history and we all learn more about how well this works.” Compounding that difficulty is that reactionary elements in the bureaucracy and special-interest groups seem determined to strangle the ISA concept in its cradle.

By withholding the most-relevant information, the Star may be helping them achieve that goal.

The original post overstated this value.